https://www.idausa.org/campaign/farmed-animal/speciesism-the-root-of-animal-oppression/

We live in a world where we share our homes with some species, eat others, and exploit still more in myriad ways, depending on what we’ve been taught about how we should see and treat different species, and whether we should consider ourselves superior to them. Unfortunately, the misguided belief that some species are worth our moral consideration and protection and others aren’t is known as speciesism, and it’s causing immeasurable harm.

What is Speciesism?

Speciesism is a form of discrimination that considers one species superior to others. This mindset is based on the belief that humans have the right to dominate, use, and kill non-human animals for their own benefit.

The term “speciesism” was coined in the 1970s by British psychologist and animal rights activist Richard Ryder, who introduced it in a pamphlet distributed as part of a campaign against animal experimentation in Oxford, England.

Why Is Speciesism a Form of Discrimination?

Like racism, sexism, homophobia, and all forms of discrimination against certain groups, speciesism devalues individuals based on arbitrary characteristics — and in the case of animals, their level of intelligence, their appearance, and if they have fur, feathers, and fins, or whether they walk on four legs instead of two.

This perspective perpetuates the idea that we have the right to use, exploit, and kill other animals simply because they’re different from us.

What Does Speciesism Look Like?

Speciesism is often the first form of discrimination we’re taught, and it manifests in two ways. The first is the belief in the supremacy of the human species over all other species. The second is viewing only certain species — such as animal companions and some wild animals — as worthy of care and protection, with some even considered part of our families. In contrast, most other animals are disregarded, and many are enslaved, tortured, and treated as commodities for food, entertainment, fashion, research, transportation, and much more.

Farmed animals are often depicted in marketing for food products as trivial, cartoonish characters, which strips them of their dignity and status as feeling individuals with their own personalities and preferences. Small family farms tend to be romanticized as wholesome places where animals live happy lives and are cared for by farmers. In reality, the basis of all animal farming is the exploitation and killing of sentient beings. Still, humans have compartmentalized their ethical views, allowing us to rationalize the cruelty and violence inflicted on animals we might otherwise be fascinated by and care about, all for our pleasure, convenience, advancement, habits, traditions, and tastes. Although it has been scientifically proven that humans can survive and thrive on a plant-based diet, most continue to consume the flesh, milk, and eggs of animals because we’ve been conditioned to believe that it’s “normal, natural, and necessary.”

Animal companions and certain wild species are granted some legal protections, while all other animals are not. Cruel practices and mutilations without anesthesia, such as castration, tail docking, burning off horns, and extreme confinement, are inflicted on farmed animals like pigs, cows, chickens, goats, sheep, and turkeys, yet would be considered horrific abuse by most in Western culture if done to dogs or cats.

If we would never subject a dog or cat to these practices, nor send them to a slaughterhouse to end their life, we must recognize that no animal deserves to be used or enslaved by us, nor to have such pain and terror inflicted upon them. Even the desire to keep some animals as companions has led to their exploitation through breeding and selling, prioritizing profit over their well-being, which inevitably results in neglect, abuse, and often death. Beagle dogs and rabbits, usually seen as ‘pets,’ are also tormented and killed in research labs.

How is Speciesism Justified?

Humans often try to justify their oppression of animals by saying that humans are the most intelligent species. Yet many animal species possess sensory and physical abilities that humans do not have.

For example, bats use echolocation — the ability to use sound waves to navigate and find objects — to navigate in complete darkness. Tiny wrasse fish can recognize themselves and others in a mirror, joining chimpanzees and dolphins in this rare skill. Octopuses excel at problem-solving and camouflage, altering the texture and color of their skin to blend into their surroundings. Birds like the Arctic tern navigate thousands of miles using environmental cues, including the stars and the Earth’s magnetic field.

Chickens can recognize faces, form social bonds, and have memory and problem-solving skills on par with many other birds and mammals. Cows demonstrate empathy and many other complex emotions and can also solve puzzles. Pigs can navigate mazes and exhibit emotions and intelligence equivalent to a 3-year-old child.

Regardless, is intelligence truly the measure of whether someone deserves to be protected from harm by others? Some cognitively impaired humans are less intelligent than many animals. Does that mean we can also use and kill them? Of course not. No individual should be required to justify their right to safety and protection from human harm based on their cognitive or physical abilities.

How Can You Be Anti-Speciesist?

Whether human or non-human, each individual thinks and feels and has their own subjective experience of life, deserving the right to share this planet with us without being dominated by us. Unlike all forms of discrimination that focus on our differences, we must focus on what all species have in common — our will and desire to live and be free, and our capacity for pain, suffering, and joy.

If we would not tolerate discrimination and harm based on race, gender, or other differences, we must apply the same reasoning to speciesism and view it as equally unjust.

To embrace liberation, justice, and compassion for all Earthlings, live vegan—the principle that calls on humans to live without exploiting any other animals.

***********

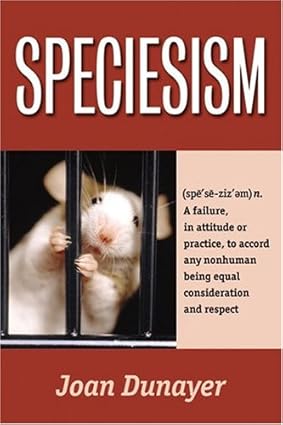

Excellent book on the subject, for more in-depth study:

https://www.amazon.com/Speciesism-Joan-Dunayer/dp/0970647565

Ryce Pub., 2004 – 204 Pages

Defining speciesism as “a failure, in attitude or practice, to accord any nonhuman being equal consideration and respect,” this brilliant work critiques speciesism both outside and within the animal rights movement. The author demonstrates that much of the moral philosophy, legal theory, and animal advocacy aimed at advancing nonhuman emancipation actually perpetuate speciesism. Speciesism examines philosophy, law, and activism in terms of three categories: “old speciesism,” “new speciesism,” and species equality.Old-speciesists limit rights to humans. Speciesism refutes their standard arguments against nonhuman rights. Current law is old-speciesist — legally, nonhumans have no rights. Dunayer shows that “animal laws” such as the Humane Slaughter Act afford nonhumans no meaningful protection. She also explains why welfarist campaigns are old-speciesist.

Instead of opposing the abuse or killing of nonhuman beings, such campaigns seek only to make abuse or killing less cruel; they propose alternative ways of violating nonhumans’ moral rights. Many organizations that consider themselves animal rights advocates engage in old-speciesist campaigns, which reinforce the property status of nonhumans rather than promoting their emancipation.New-speciesists espouse rights for only some nonhumans, those whose minds seem most like those of humans. In addition to devaluing most animals, new-speciesists give greater moral consideration and stronger basic rights to humans than they do to any nonhumans. They see animalkind as a hierarchy, with humans at the top.

Dunayer explains why she categorizes such theorists as Peter Singer, Tom Regan, and Steven Wise as new-speciesists.Nonspeciesists advocaterights for every sentient being. Speciesism makes the case that every creature with a nervous system should be regarded as sentient. The book provides compelling evidence of consciousness in animals often dismissed as insentient — such as fishes, insects, spiders, and snails. Dunayer argues that every sentient being should possess basic legal rights, including rights to life and liberty. Radically egalitarian, Speciesism envisions nonspeciesist thought, law, and action.